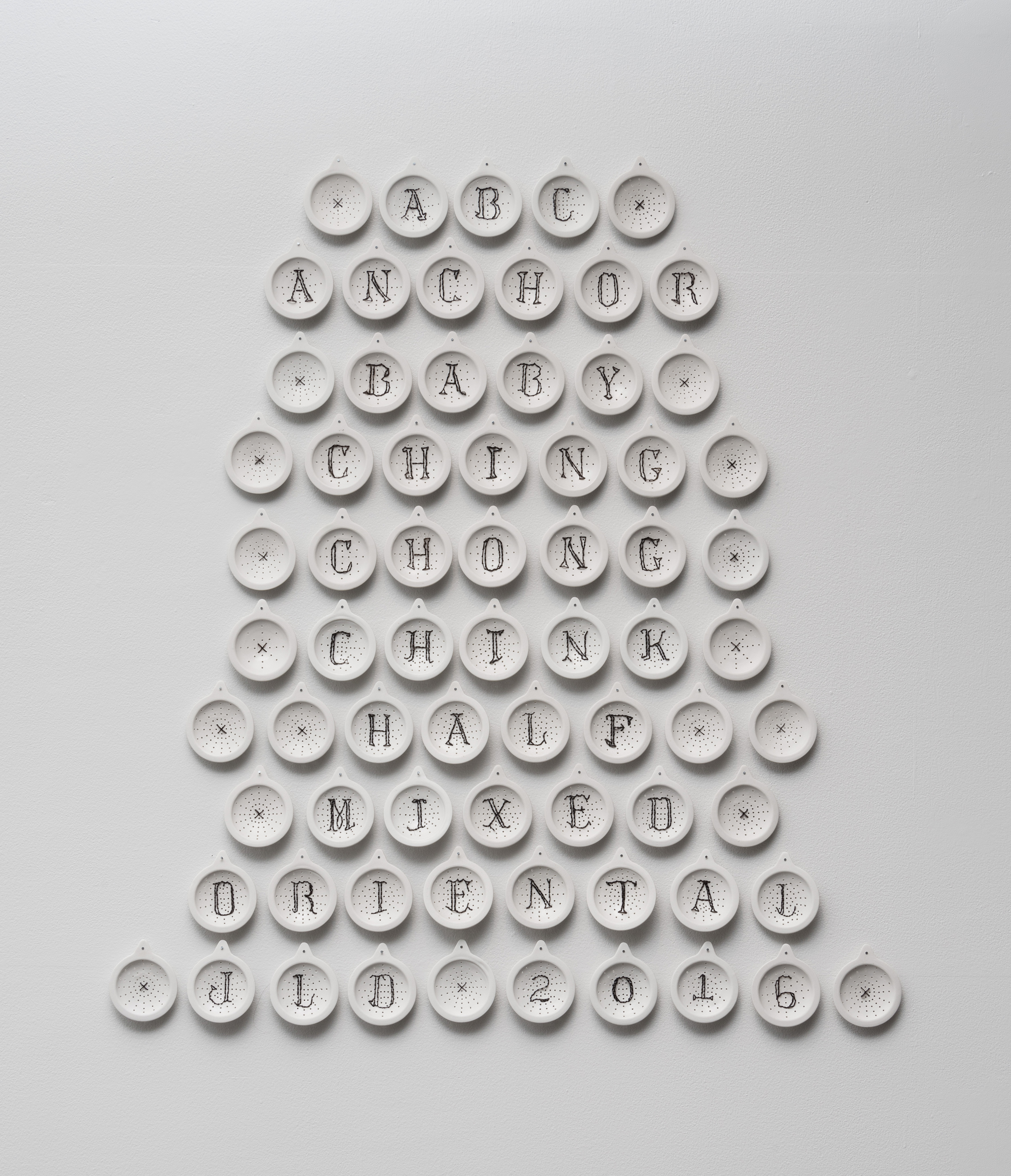

Blackwork, 2016

Most scholars agree that blackwork embroidery originated with the Moors, but was described as “Spanish work” throughout Europe - the African history erased in the hands of white women. Even so, I was drawn to the innocence of embroidery, especially as a traditional pastime for young girls so different from the pursuits expected of girls in the digital age. Globally, girls still labor to be seen as equals, find their voice, defend their choices, while being endlessly critiqued. And yet, girls are increasingly finding solidarity in younger political and cultural role models, especially those of color. Blackwork, then, is an intersection of labor, innocence, girl power, and white ideals of beauty and industry.

The painstaking, meditative aspect of embroidery reminded me of the slowness of hair growth. Across the world, women and girls grow their hair for money. Different nationalities are prized for their virtues, but the hair dealer I met in China said Chinese hair was the best for wigs because it can mimic any texture or style, and be transformed into any color. We live in a world where identity can be manufactured and appearances appropriated without concern or even awareness. We question and desire authenticity of the other.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()