RIPENING, 2025

In RIPENING, artist Jennifer Ling Datchuk asks us to consider the cost of women’s labor in our everyday lives. Through five thematic sections—Protest, Rest, Labor, Exploitation, and Ripening—Datchuk weaves together her personal history as a Chinese American woman and new mother with broader questions about gender, race, and power.

The granddaughter of factory and service industry workers, Datchuk’s perspective is rooted in stories of hands that stitched, assembled, and served. But how is labor defined when it is unpaid, invisible, or done in silence? How do histories of service work, migration, and motherhood continue to shape how women are seen—or not seen? Trained in ceramics but working across media, Datchuk uses hair, porcelain, video, and performance to transform these questions into spaces of collective care, resistance, and reflection.

Through newly created and reimagined installations for the NMSU Art Museum, RIPENING uplifts often-unheard stories—especially those of Asian American women and female laborers in the Southwest. These works reflect on the physical and emotional realities of being a woman and mothering in 2025, asking: what is the value of time, growth, and expectation under capitalism? How do women’s bodies become sites of both creation and control, of care and constraint? Datchuk invites us to question how the most intimate forms of labor—like nurturing a life—are often the least visible, yet the most deeply felt. What happens when those silenced begin to speak, or when their care becomes a force for change?

Ripening:

As a woman navigating the reproductive complex for over a decade–from endometriosis and infertility to pregnancy and postpartum–and as an artist questioning both the policing of women’s bodies in our society and the value placed on our labor in the global economy, I see women as the source of everything, yet witness how systems fail to support us. “Ripening” speaks to growth and transformation: fruits and vegetables maturing for harvest, physiological and emotional changes that women and children undergo simultaneously during pregnancy. From seed to soil, infertility to fertility, from the ways we carry life to the labor and care that follow.

Protest:

I was taught at a very early age to “eat bitterness” – the Chinese idiom that describes enduring hardships without complaint, to suffer in silence, to obey, and ultimately to remain in submission. No matter how empowered we feel, or how much we attempt to reclaim, women still find themselves navigating choices dictated by narratives we did not create. Deep within my DNA, and in the muscle memory of the assembly line, I carry my grandmothers' hopes and tell the stories of how their labor helped build what was once stamped “Made in America”.

Rest:

In today’s late capitalist system, how do we care for ourselves when work is survival? My grandmothers were hustlers. Their workday did not end in the factory but continued at home with piecemeal jobs, tending to children, and managing domestic chores. I never knew them to prioritize self-care nor were their contributions acknowledged as labor. In reclaiming these forms of work, we begin a cultural unlearning—observing how our bodies record time and giving ourselves permission to rest. More than ever we openly share this exhaustion, but there is also a tide of change. The affirmations spoken by a new generation offer hope for building presence, care, and connection across generations.

Exploitation:

Between Asian communities scattered throughout the American Midwest, South, and Southwest, I know the long drives to find Asian groceries, familiar foods, services, and comforts of home. I cry at the taste of a steaming pork bun, the rough scrub of an auntie’s hands washing my hair, and her loving critiques in Toisan—the dialect of Guangdong province and my childhood home. Despite the comfort they offer, these “Chinatowns” collapse Asian identities, flattening differences while housing countless diasporas of labor in pursuit of the American dream. How many hands are exploited to make these spaces feel like home? Life feels fragile, inequalities widening, fears of xenophobia persist. When does invisible labor become visible to others?

RIPENING at NMSU was made possible in part with support from The Community Foundation of Southern New Mexico, Devasthali Family Foundation Fund; Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts; Ruiz-Healy Art, San Antonio / New York; Guillermo Nicolas; United States Artists, NMSU College of Arts & Sciences; Southwest and Border Cultures Institute; Friends of the University Art Museum; and several private donors.

Eat Bitterness, 2023

eat (verb)

: to take in through the mouth as food: ingest, chew, and swallow in turn

: to destroy, consume, or waste by or as if by eating

bitterness (noun)

: sharpness of taste; lack of sweetness.

eat bitterness:

a Chinese idiom to describe enduring hardships without complaints, or even to suffer

As the granddaughter of factory workers, my Irish American grandmother was just one of a handful of women who worked the assembly line of a car manufacturing plant, and her Chinese grandmother worked in a sewing factory, located deep within the alleys of Chinatown, for an American retailer. Their hands adapted through the constant path and rumble of the industrial sewing machine and as cars and the assembly-line work modernized with computers and automation. My grandmothers faced poverty, political and social oppression, and personal trauma. Eat bitterness. They were both tough, independent women during a time when women weren’t supposed to be either.

I use porcelain to describe dualities—this material can capture both fragility and resilience. I use adornments, blue and white patterns, reflective surfaces, synthetic and human hair in installations, objects, and video work to explore the global inequalities of labor, notions of girlhood, and forms of protest.

Much of my work focuses on how women specifically embody time: the phases of the moon and the menstrual cycle, the exaggerated weight of waiting and quarantining, the slow growth of hair, the thresholds we cross and the unknown spaces we withstand, and the many “luck” objects we create to hold and use while hoping for a better future or circumstances.

Braiding pain and perfection, these objects amplify female voices, reconstruct our identities, and celebrate our truths. Refuse to eat bitterness. Deep within my DNA and the muscle memory of the assembly line, I also feels my grandmothers' hope.

Jennifer Ling Datchuk: Eat Bitterness, 2023

Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts

May 20, 2023–September 17, 2023

Curated by Rachel Adams, Chief Curator and Director of Programs

Learn more: Bemis Center for Contemporary Arts

Later, Longer, Fewer, 2021

“Later, Longer, Fewer” is the translation of a 1970s Chinese propaganda poster that encourages later marriages, longer intervals between children, and fewer children as a means to liberating women. Women were to take advantage of birth control to curtail the country’s birth rate – a “benefit” that led eventually to China’s one-child policy. Given the culturally instilled value of boys over girls, “fewer” took on a new meaning.

This message suggests that women have the power and access to resources in order to make these decisions in the first place. Given how the United States has so politicized birth control, I began to work with the ironic tension inherent between the expanded opportunities available with modern health care and the systemic inequities that continue to hold women back globally.

Much of the work focuses on how women specifically embody time: the phases of the moon and the menstrual cycle, the exaggerated weight of waiting and quarantining, the slow growth of hair, the thresholds we cross and the unknown spaces we withstand, and the many “luck” objects we create to hold and use while hoping for a better future or circumstances.

The societal, cultural, and political systems women navigate are explored here through porcelain, adornment, blue and white patterns, reflective surfaces, and synthetic and human hair via installation, objects, and video. In juxtaposition, pieces explore how relegation to the domestic, mother-sphere annihilates the innocence of girlhood and locks women into a controlled space of servitude. As an Asian woman, using race as a lens further narrows the circles we are allowed to operate within.

No matter how empowered, no matter what we have attempted to reclaim, women still find themselves moving back and forth among choices dictated by narratives we did not create.

Tame, Filmed and Edited by Walley Films, 2021

Learn more: Houston Center for Contemporary Craft

Live to Die, 2020

Installations at Black Cube “Fulfillment Center” and “NCECA”

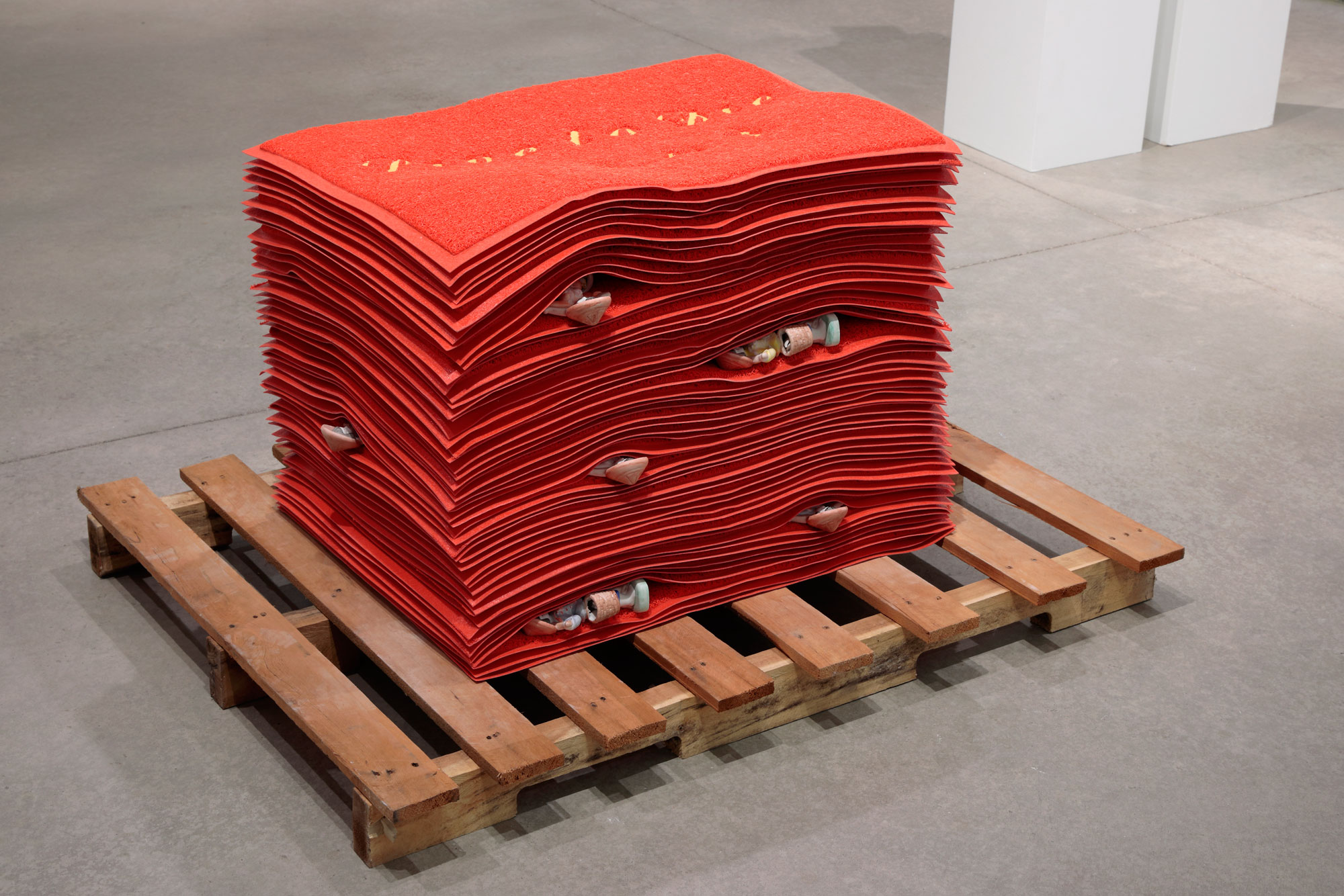

Red doormats that say "welcome" in Chinese and English are found in front of almost every Chinese restaurant and business all over the world. These mats are markers for crossing thresholds, the objects below our feet that welcome or receive us as we work, spend, desire and consume. This red is symbolic of good luck and fortune in Chinese culture but synonymous with anger and passion. The pallet rack with the stacks of mats embossed with the phrase "Live to Die", a morality statement found at the bottom of alphabet samplers from the 1800's. This phrase stitched onto linen by the hands of young girls who probably did not fully understand the darkness and futility of these words.

![]()

![]()

Disrupting the perfect stacks of doormats are golden figurines of a young Asian girl, barefoot, wearing a rice pickers hat, and carrying a heavy load on a shoulder yoke. They become buried under the weight of the mats, hidden and obscured but we know they are there. Her labor and presence invisible to the objects we so easily order and buy but so much a part of this cycle of consumption and fulfillment.

![]()

![]()

I often think of the label “Made in China” and how its associated with objects that are cheaply and poorly made. What makes their labor and bodies any less than that of American labor? We need to acknowledge and confront are the capitalist systems in place that have created an American ruling class that for decades have put profits over people and continually exploit global inequality.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Learn more: blackcube.art

Disrupting the perfect stacks of doormats are golden figurines of a young Asian girl, barefoot, wearing a rice pickers hat, and carrying a heavy load on a shoulder yoke. They become buried under the weight of the mats, hidden and obscured but we know they are there. Her labor and presence invisible to the objects we so easily order and buy but so much a part of this cycle of consumption and fulfillment.

I often think of the label “Made in China” and how its associated with objects that are cheaply and poorly made. What makes their labor and bodies any less than that of American labor? We need to acknowledge and confront are the capitalist systems in place that have created an American ruling class that for decades have put profits over people and continually exploit global inequality.

Learn more: blackcube.art

100 Years, 100 Women, 2020

100 Years, 100 Women, 2020

Park Avenue Armory, New York, NY

Curated by Dr. Deborah Willis

This year we celebrate the 100th anniversary of the ratification of the 19th amendment that guaranteed all American women the right to vote. In 1920, this did not give all women the right to vote, as Asian American women could not vote until 1952, Native American women could not vote in all 50 states till 1957, and a majority of Black women could not vote till 1965.

We vote to create change and see our communities and values reflected in our elected officials. Americans are being confronted with their icons, their fetishes, their appropriations and the erasure of HERstory. Voter suppression through barriers of registration, id requirements, lack of early voting, laws, intimidation and systemic racism are keeping people from exercising their right to vote. These hits keep coming but this work to guarantee the right to vote is multigenerational, multicultural, and intersectional and absolutely necessary to dismantle power structures and build an equitable and inclusive United States.

Learn more: www.100years100women.net